It’s officially summer here at the University of Missouri. Grades are in. Evaluations complete. My Mozilla Hubs space is fleshed out, and I’ve fulfilled Unity’s programmer curriculum! As for the University of Arizona, my satellite campus, we in the Asian Studies department have another week to go. Translations are movin along beautifully and I’m excited to continue sharing my work on the Hyakunin Isshu with you folx.

Bear with me here. I spent the day in kidspeak and the aftereffects linger! So understand that my proceeding ramble is just my process of transitioning from an audience of middle graders to one of friends.

Hey there, fellow curious minds and history enthusiasts! Today, we’re embarking on an exciting adventure through the captivating world of printing history. Join me as we dive into the awe-inspiring tales of Japanese, Chinese, and Western printmaking, and unravel the artistic tapestry that sets each tradition apart.

Picture this: ancient scrolls, meticulous calligraphy, and the mesmerizing art of storytelling come to life in the lands of Japan and China. The pages whisper of emperors, warriors, and mythical creatures, transporting us to a realm of cultural depth and aesthetic elegance.

In the East, printing was an art form, an expression of identity and tradition. Delicate strokes of ink crafted by skilled artisans breathed life into scrolls, captivating the hearts of generations with their beauty and symbolism. From the intricate Mayan hieroglyphics to the graceful Arabic calligraphy, each script told its unique tale, preserving the wisdom and dreams of its people.

Now, let’s take a hop, skip, and a jump to the West, where a revolutionary invention changed the game forever. Enter the Gutenberg press! The clanking of metal letters, the rhythmic dance of the press, and the scent of freshly printed pages filled the air. Johannes Gutenberg’s ingenious creation unleashed a torrent of knowledge, shaking the world with its impact.

Western printmakers reveled in this newfound power to disseminate information widely. Pamphlets, books, and newspapers flooded the streets, igniting the flames of intellectual revolution. Ideas spread like wildfire, shaping minds, and inspiring revolutions that echoed through the ages.

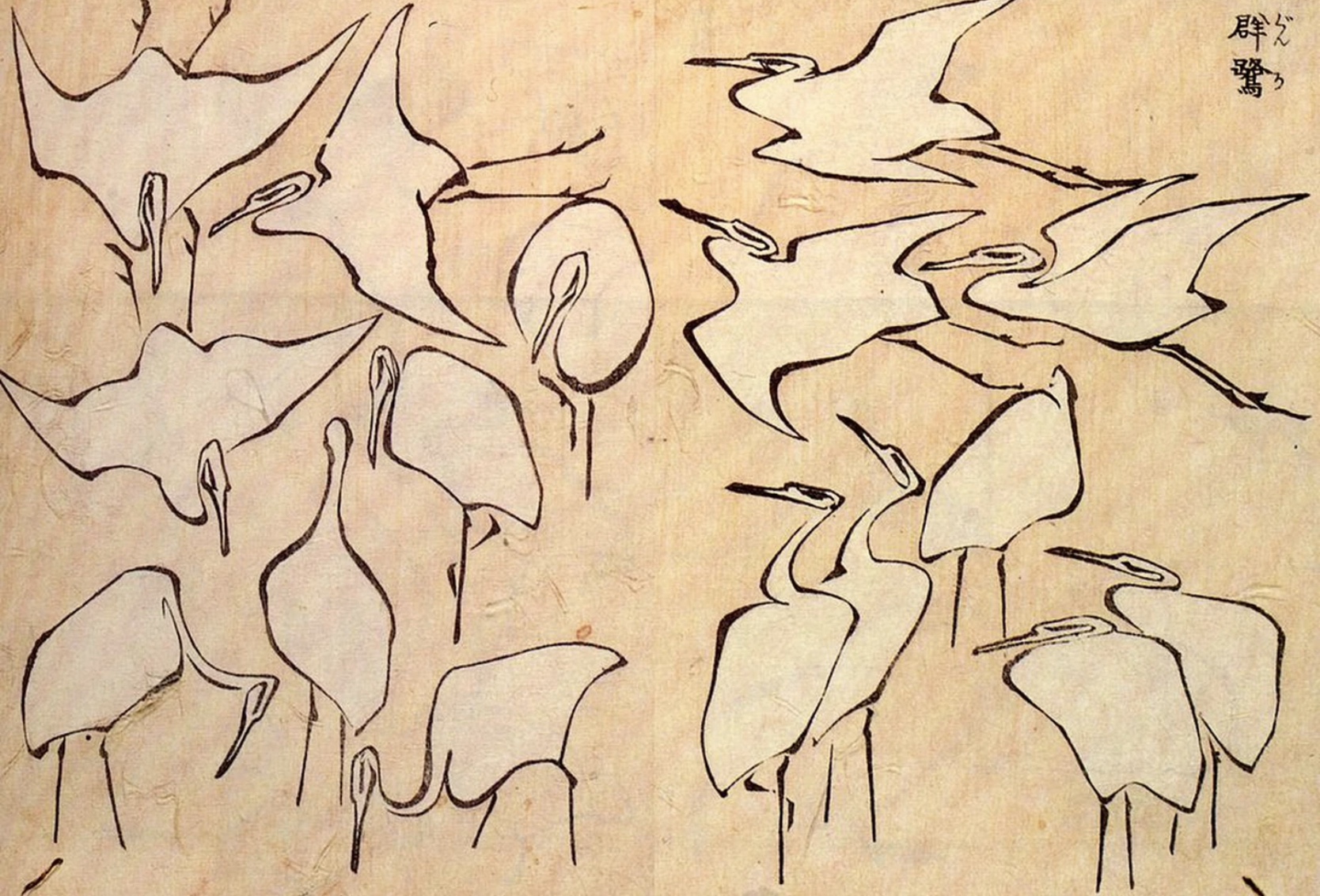

But hold on tight; our journey doesn’t end here! We’ll explore how the East clung steadfastly to its centuries-old traditions of handmade artistry. The Chinese woodblock printing, with its meticulous precision, created dazzling illustrations of ancient tales. Meanwhile, Japan’s woodblock masters conjured vibrant scenes of theater, nature, and folklore.

With every turn of the page, you’ll feel the distinct essence of each culture, as the aesthetics paint a vivid picture of their unique identities. From the ornate manuscript illuminations of medieval Europe to the serene beauty of ukiyo-e prints, we’ll be transported through time and space.

Ok. Cutting the charade, media history fascinates me deeply. Like, if there were a way to analyze user experience throughout time, measuring engagement, likability, usability, etc then buckle me in and ship me on the next Time Machine to Ts’ai Lun’s printshop. Knowing me I’d forget my wallet… wonder if alum accepts bitcoin… jokes aside what I would give to critically evaluate those moments throughout history which ripple forward reaching us today. We’re all too complacent neglecting the fact that much of our recorded history is just about as much erasure of other histories as it is preserving.

I’d like to linger with this in mind as we move forward over these next couple of days. As we we work through the known histories of Eastern and Western printing, I invite you to reflect on this notion of erasure. What is being erased in the process of preservation? Hegel invited us to use a set of tools when considering what is and what was. In Being and Becoming, I think it was.

Hegel’s notion of “Aufheben” or sublation offers an illuminating framework for examining histories of what is known and histories of what was erased. When investigating what is known, sublation encourages critical scrutiny of established narratives, recognizing their partiality and limitations, while preserving valuable insights that contribute to our comprehension of the past. It entails surpassing one-sided viewpoints to arrive at a more comprehensive understanding that transcends mere opposition or negation. In the context of histories of what was erased, sublation compels us to confront suppressed, forgotten, or marginalized aspects of the past. By integrating these neglected narratives into the larger historical framework, sublation seeks to redress historical injustices and reconstruct a more inclusive and nuanced account of human history. Hegel’s concept, therefore, invites a dialectical engagement with the complexities of history, moving beyond the binary of presence and absence, and fostering a continuous process of enriching our knowledge and comprehension of the human experience.

So that’s not so hard, is it? 😅

That’s why you’re here, right? We’re challenging one another and hoisting each other up to fulfill become better humans.

Over the next few days we’re going to challenge one another through the act of sublation as we discuss the history and development of media and print culture from China, Japan, and Western Europe.

What we’re talking about

The idea of highlighting media artifacts throughout world history that have impacted or refused to impact the globe is a fascinating lens through which to explore the complexities of human communication and cultural development. By examining the contrasting paths taken by the Gutenberg press and the Japanese/Chinese printers, we can gain insights into the social, political, and technological factors that shaped the evolution of media in different regions.

- Context and Cultural Factors:

The celebration and widespread development of the Gutenberg press can be attributed to the unique historical context of Europe during the Renaissance and the subsequent Age of Enlightenment. The printing press emerged at a time when there was a growing demand for knowledge dissemination, fueled by a newfound curiosity in science, philosophy, and literature. European societies were experiencing a cultural shift, with the rise of humanism and a focus on individualism, encouraging the spread of ideas through printed materials.

On the other hand, the preference for handmade content by Japanese and Chinese printers was influenced by cultural traditions and value systems deeply rooted in their societies. Both Japan and China had longstanding traditions of calligraphy and artisanal craftsmanship, emphasizing the beauty of handmade creations and their connection to spiritual and cultural aspects of life. In these cultures, the process of creating written works was regarded as a revered art form, making the shift to mass-produced printed materials less appealing.

- Language and Writing Systems:

Another critical factor in the contrasting developments lies in the differences in writing systems and languages. Chinese and Japanese writing systems are logographic, consisting of characters that represent whole words or concepts. The complexity of these scripts made the process of developing movable type more challenging and less practical than in alphabetic systems like the Latin-based languages used in Europe. - Sociopolitical Influence:

The sociopolitical climate of each region also played a role. Europe’s fragmented political landscape allowed for more diverse printing practices, leading to a competitive market of ideas and information. In contrast, China and Japan, under strong centralized governments, maintained strict control over the production and dissemination of written materials, limiting the spread of mass-printed texts. - Technological Adoption and Resistance:

In Europe, the Gutenberg press was embraced as a disruptive technology that offered economic benefits and accelerated knowledge-sharing. On the other hand, Japanese and Chinese cultures exhibited a resistance to embrace foreign technologies, as it could be seen as a threat to their cultural identity and the artisanal value of traditional content creation. - Long-Term Impact:

While the Gutenberg press revolutionized global communication and significantly contributed to the spread of knowledge and ideas, the Japanese and Chinese printing traditions preserved cultural heritage and the art of craftsmanship. Both paths influenced the course of history in their own right, shaping the development of literature, culture, and information dissemination in their respective regions.

The critical analysis of highlighting media artifacts throughout world history that have impacted or refused to impact the globe provides valuable insights into the interconnectedness of technology, culture, and human society. The celebration and development of the Gutenberg press in Europe and the preference for handmade content by Japanese and Chinese printers reflect the complex interplay of historical context, cultural traditions, technological factors, and sociopolitical influences. Understanding these dynamics can help us appreciate the diverse pathways of media evolution and their lasting impact on global communication and culture.